April 12, 2010

Cynthia W. Shelmerdine

Professor and Chair

Department of Classics

The University of Texas at Austin

Austin, Texas 78712-1181

(512) 471-5742

cwshelm@mail.utexas.edu

Dear Professor Shelmerdine:

I have spent the last few days happily pouring over The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age, (ed. Cynthia Shelmerdine, Cambridge University Press, 32 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10013-2473 2008) looking for the driving force of human events, and I am writing with two purposes, one serious and the other rather less so.

My interest is in demographics and the survival of societies particularly as affected by social norms. What I have noticed is this:

For argument’s sake, let us say people face the old choice of Achilles between peace and glory. That is not to say most of us have a fair chance at either; it’s just a place to start.

If you choose peace, you may be able to have it at the cost of a great deal of hard work, but if somebody else decides you are his ticket to glory, you are probably out of luck.

That leaves glory. Glory is awarded by a society that is large. If you limit your social circle to a few dozen, you may be popular, but if nobody outside that circle hears of you, sorry, no glory.

So glory depends on a society larger than a few dozen, say at least a few hundred or thousands. And that society, however aggressive it may be toward other societies, must be internally cooperative. All must share the same goals. All must respect each other. That means that there must be a social pool of hundreds or thousands and usually much larger. And there is the problem. I observe two numbers.

The first number is a critical population size. It appears to be between 200 and 800. Whether that is adults or total I am not clear on as my sources are coy on the point.

The next number is a time. It is about 150 years. What happens is that when a population exceeds the critical size a process starts that cycles each 150 years. When a cycle is complete, something is likely to change. Sometimes the change is peaceful. Frequently there is violence. But one way or the other the critical social group has an increased risk of vanishing.

The first cycle is fairly mild. The second is generally catastrophic. So few societies survive the second cycle that it is hard to predict, but they can go on to a third and fourth cycle. Those that survive four cycles are extremely rare.

I find support for this observation in the histories of Egypt, Southern Mesopotamia, China, Japan, the Mayans, Chaco Canyon, Easter Island and Long House valley, the last three pooled to have numbers big enough to be interesting.

Here, for instance, is Southern Mesopotamia.

Information taken from R. H. Carling THE WORLD HISTORY CHART International Timeline Inc. Vienna, VA 1985. The experience of Southern Mesopotamia. The vertical axis is the chance of an empire of any age continuing to rule locally for another 50 years. The horizontal axis is the ages of the empires. I broke the Ottoman Empire into two, because their Janissary elite came from two different sources during the early and late empire.

Slick, eh? It would be bad enough if that were a graph of surviving empires. In fact it is a graph of the chance an empire of any age has of surviving the next fifty years. The 2 cycle 300 year pattern dominates the graph. The reason the line does not go straight out and then straight down is that by and large these empires were already somewhere along their life span when they took over the area.

If you look at the Maya, Roman, Chaco line, it looks the same. Chinese and Japanese dynasties mostly last two cycles but a few of each drop out at one cycle. Long House Valley lasted two. Apparently the Greenland Norse lasted three. They were clearly more numerous than the critical level, but they were dispersed far along the coast of Greenland. Effectively they were not a single social pool. Easter Island lasted four. They were above the critical level but they were broken into smaller tribes. Remember those big statues? They represented competing families, according to Thor Heyerdahl in Aku Aku. They came very close to being able to have glory and long life.

Here is their experience:

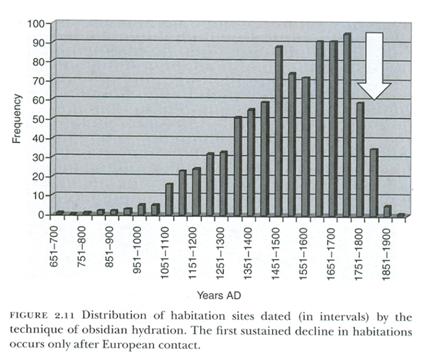

Chapter 2 Terry L. Hunt and Carl P. Lipo ”Ecological Catastrophe, Collapse, and the Myth of “Ecocide” on Rapa Nui,” Questioning Collapse, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2010

As you see, they started out as a small community, grew, had a population decline at about mid course and then a catastrophic fall after two more cycles. I see no reason to blame the advent of Europeans.

For the other graphs go to http://nobabies.net/Albuquerque%20poster.html or just go to nobabies.net and click on the March 25, 2010 entry. The data on Greenland is currently too lean to graph. Consider it an anecdote.

Of course you have noticed what has bothered me for a long time. Where does Greece fit in?

Well Greece presents two problems. For one thing it is pretty easy to draw a line around Easter Island and say everything inside this is Easter Island, and they are all in contact, and everything outside isn’t. Come back after a couple of centuries and the line is still good. That’s hard to do with Greece. In fact my younger brother tells me that Tarpon Springs, right up the road here, is a Greek polis. They didn’t go through immigration and naturalization procedures. They just came in, built a town and started taking sponges. There are not only shifting alliances and trade, they are always hopping into their boats and going places. When a piece of pottery turns up far from where it is typically found, does that mean the pot moved, the artisan moved or a whole population moved? It’s difficult to figure out what the mating pattern was. In fact it is so difficult that if I put up all the numbers and found the pattern that is so obvious elsewhere I wouldn’t believe it myself. As the elephant’s child said, “This is too buch for be,” despite any number of depopulation events.

The second problem is that the Greeks secluded their women. Plato records Socrates as deploring the custom, but it had at least the opportunity to limit mating pool size. But just who secluded women and when? We typically think of Minoan women as being brazen hussies striding around with bare chests, but as the book points out, they are not typically represented as being in the company of men. In the frescoes they are shown with white skin suggesting they didn’t go out much. They were depicted as barefoot suggesting the same thing. The fresco of the woman with an injured foot might be a cautionary tale. And she and her companions are veiled. It might be imprudent to say that altogether this means that women were secluded by the Minoans, but it would certainly be imprudent to claim the opposite. And if the Minoans did it and the classical Greeks did it, any and all intervening ages might have.

Now one problem makes the social pool larger and the other makes the social pool smaller. With both of those to draw on, you can explain anything. That means there is no relevant data. This is a pity.

That said, however, there is a graph on page 234.

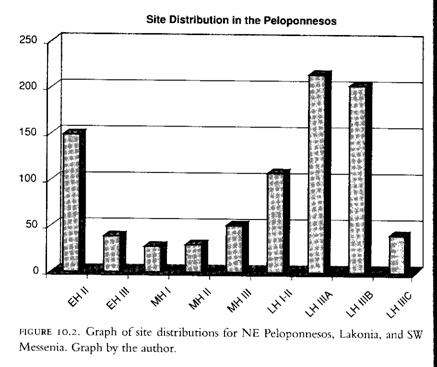

Graph is from The Cambridge Companion to the Aegean Bronze Age, (ed. Cynthia Shelmerdine, Cambridge University Press, 32 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10013-2473 2008 chapter 10 “Early Mycenaean Greece,” James Clinton Wright page 234 fig. 10.2. It shows the number of settlements in the northeast Peloponnesos, Lakonia and southwest Messania during various ages. Middle Heladic III (MHIII) begins in 1700 BC and Late Heladic IIIC (LH IIIC) ends shortly after 1100 BC.

Now you are talking my language. Graphs I understand. The smooth swoop and dive is typical of other population curves, although these are populations of towns, not of individuals. The latter boom and bust come all around to being about 600 years or four cycles. It might be a little longer. But the towns are not necessarily in synchrony as a population representing a social pool of individuals would be. From the looks of the beginning of the graph, we are just coming off one major cycle and going into another. Compare the time course of the second surge and crash with the surge and crash of Easter Island.

So I am encouraged to think that the usual process is in action in Bronze Age Greece, just like every other time and place I have looked. (Except Britain, which is a special case. Women could own land, were thus tied to the land and likely to marry men who owned land nearby. In that society rich people actually had more babies than poor people, which led to and probably caused the Industrial Revolution.)

The root cause has to be genetic. This stuff you hear about the bigger the gene pool the better and healthier, there is no evidence for it. The evidence is quite the contrary. To have babies it isn’t enough to have sex. It has to be sex with the right person. Since fertility is something of such enormous importance, you would think that every geneticist who heard about this would drop everything else and try to get to the bottom of it. There are some problems still to be worked out such as the specifics of maximum safe gene pool size, the mechanism for infertility and how in the world you pull out of the dive before going into the floor. There is work to be done once the professional geneticists take an interest. Alas, my experience has not been encouraging.

So there it is. That is the driving force of history. If it is true, and I am quite certain it is, there must be evidence everywhere you look. I hope it proves useful in your own work.

Now for the fun stuff. If you have soldiered on this far into the letter and groan for an end, stop at the end of this paragraph. Go to my website Nobabies.net, where I put up my evidence and letters like this, if you want more evidence or further thoughts on the matter. If you are having fun, then by all means continue.

There are four things I have wondered about Bronze Age Greece that I did not find in the book.

The first is the double bitted axes. When I was at Knossos years ago there were such axes of various sizes on display including some so large that even I could not wield one. Maybe they inspired the Paul Bunyan stories. The top of the axe reminds me a little of the outline of the top of Mt. Ida, the sacred mountain. It also reminds me of what you call Horns of Consecration, stylized bull horns of religious significance. At the museum there was no mention of the context in which they have been found. Is anything more known about them?

The second question has to do with warfare. I have long suspected that the Neolithic age ended and Bronze Age began when tribalism was introduced. Violence between communities could serve to restrict social pool size, stabilize populations and give the opportunity for technological advance. But I had read that among the Minoans there was no war, no coercion of any sort. It was a cooperative society. What is the current take on that?

On the mainland, there was a house shown on page 29 that seems sweet and bucolic enough with a balcony up front, stairs running up just inside the front door and a main room in back. But it is a fort. The front door is displaced all the way to the left as you face the house. That gives an advantage to a right handed man with a sword guarding the house against a right handed intruder with a sword. Meanwhile the wife and children can run up the stairs to the balcony to drop things on the intruder if he steps beyond the balcony or lift a floorboard and drop things on his head if he does not. Furthermore the defender can go up one step on the stairs and get a height advantage. I have occasionally tried to design a defensible house, but I never came up with anything that good. But that was the mainland.

There was an official called a key bearer? Did they have locks and keys?

The third question has to do with Dionysus. He is mentioned among the Mycenaeans but not the Minoans. He is god of drama, of course. The question is whether drama was an activity that far back. At Knossos they showed us a flight of broad steps leading up to the main entrance as one came in from the harbor. And seated there one could watch the harbor entrance. Our guide invited us to imagine a crowd seated there when there was not much else to do, gazing to seaward waiting for some excitement. Those disposed to could have taken the opportunity of a ready made audience to put on performances. And later theaters tended to be situated in sight of the sea. No mention is made of it in the book. Is that fantasy still acceptable?

On the fourth question I am going right over the wall. You will possibly think I was brain damaged by exposure to the stories of H. P. Lovecraft at a tender age. But what about parallels between Knossos and the British Isles?

It seems clear that Greek pottery seldom if ever made its way as far as Britain in those far off days. And although the source of tin for the Bronze Age remains a bit of a mystery and Cornwall has tin, I would assume that a British source for tin has been well ruled out; such a possibility would be hard to overlook.

There are the remains of a Neolithic village in Scotland called Skara Brae, occupied around the Early Minoan period. In this town, so I am told, there is an arrangement for a stream to flow through the town and through what amounted to toilets. A similar arrangement is present in one of the apartments of Knossos, rather later but still this was a remarkable accomplishment for each society and a remarkable coincidence if they came up with the idea independently. Most Americans still used outhouses into the 20th century.

One robin – no spring.

Then there are the tholos tombs found on Crete, dating back to Early Minoan times. The first ones are roughly contemporaneous with the Newgrange structure in Ireland. The tholos was a corbelled dome with an opening toward the east. So was the core of the Newgrange edifice.

Second robin – so what?

At Knossos we were shown what we were told was a throne room. It had an anteroom that opened somewhat south of east. The anteroom was lined with gypsum, which would have made it very bright in sunlight, and it would have filled the throne room itself with a soft diffuse light. The Newgrange construction was, apparently, sheathed in quartz. The quartz crystals made it white but served no internal optical function, but the now well known arrangement of internal stones permitted sunlight just at dawn on the winter solstice to enter the innermost recesses where it produces a dramatic illumination of a triple spiral carved in a back wall and at the same time fills the chamber with soft diffuse light.

Third robin.

But the thing which amazed me most, and which I am not so sure of since I visited Knossos and Newgrange years apart, took no notes and have not seen measurements in print is a set of four essentially identical stone tubs. They are large, roughly hemispherical, and each one is cut from a single large piece of grey stone. One stands just outside the anteroom at Knossos and three are in the depths of Newgrange.

Just because they look alike does not mean they are alike, but the issue can be put to the test. The tub at Knossos should yield five numbers, height, diameter, smoothness, thickness and departure from a perfect hemisphere. Is the height of the Cretan tub the same as the height of the Newgrange ones? How different is different? Since there are three similar tubs in Ireland, that question has an answer. Each dimension of the Irish tubs, since there are three of them, has a mean and standard deviation. If the dimensions of the tub in Crete are within a couple of standard deviations, then it would be hard to deny that they are the same tradition. Then either there was direct contact or the Neolithic culture of Europe was continent wide. I think that would be interesting to know.

Of course there is one striking difference between Neolithic Britain and Minoan Crete. Representations of things are essentially absent from British art of the time. So it is not possible to suggest the culture is the same everywhere, but it seems to me that it should be possible to find or refute the existence of one more robin.

Thank you very much. Please let me know what you think about the pulse of history as I describe it.

Sincerely,

M. Linton Hebert MD

There have been 3,978 visitors so far.